Author: Emily Manoogian, PhD

Cory and Dona Mapston have been living on a shift work schedule for almost 3 decades. Cory is a sergeant in the San Diego Police Department and despite a rotating shift-work schedule, he has managed to optimize his schedule to stay healthy. Unfortunately, most people on a shift work schedule have not cracked this very complicated code of healthy living on an erratic schedule. We interviewed Cory and his wife Dona to discuss what they’ve learned over the past 28 years of living with shift-work. We will have two more posts to go through each of their schedules and coping mechanisms, but before we get into the details, it’s important to first talk about what we mean by shift work and erratic lifestyle, its prevalence in our society, and its potential impact on health.

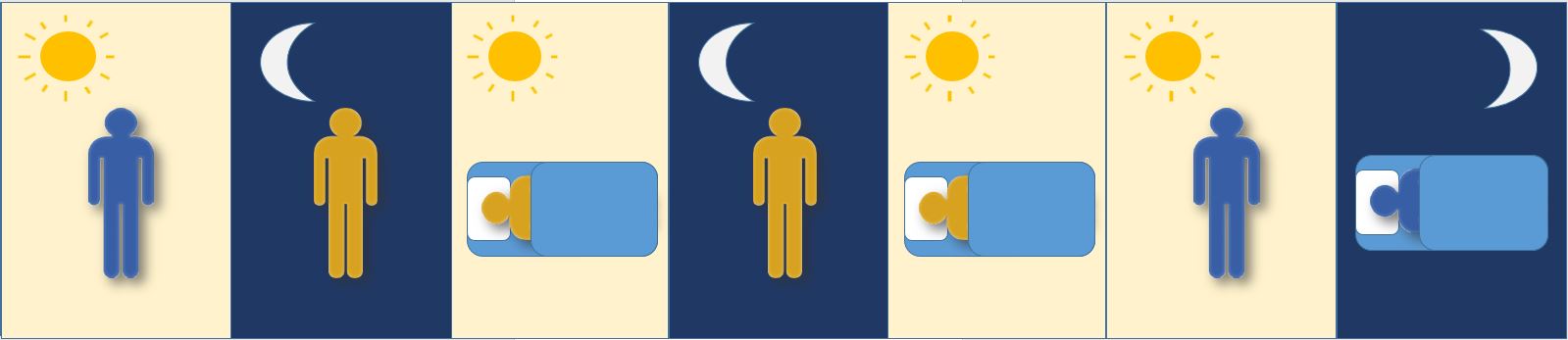

We define lifestyle as when, what, and how much you eat, sleep, move, and connect. All of these lifestyle factors (calorie intake, light exposure, sleep patterns, activity, and social interaction) are external cues that influence your internal biological rhythms. Therefore, an erratic lifestyle (long eating intervals of more than 13 hours a day, irregular sleep/wake cycles, chronic jet-lag, shift-work, etc.) can lead to chronic circadian disruption.

According to labor statistics, nearly 17-22% of the labor force in a modern industrialized country are shift-workers. As shift-work is only one mechanism of circadian disruption, the actual fraction of the population experiencing chronic circadian disruption is likely substantially higher. Some of the demographic groups that are likely experiencing circadian disruption include, but are not limited to, family members of shift workers, young mothers, caregivers for newborns and children, military forces, and college students.

Chronic circadian disruption due to erratic lifestyle can greatly increase the risk of non-infectious chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, mental health disorders, cancer, and diabetes (1). The metabolic consequences of an erratic lifestyle are two-fold: (1) insufficient nightly fasting inhibits proper glucose metabolism and (2) disruption of internal biological rhythms which in turn also leads to disrupted metabolic function (1, 2). Meta-analysis of 12 studies demonstrated that there is a significant association between shift work and diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes), and is most pronounced in men and rotating shift workers (3).

As so many people are affected directly or indirectly by shift-work, and the consequences of circadian disruption can be so severe, it is vital that we understand how to optimize our body’s rhythms and health when schedules challenge our natural rhythms.

One reason that it is difficult to provide guidelines on how to deal with shift work is that shift work can vary greatly on multiple levels. For instance, the time of the shift (morning vs night shift) will vary greatly depending on the occupation. It is also important to considered the number of shift-days per week and the structure of those days (3 days on, 4 days off; 5 days on, 2 days off; 2 weeks on, one week off; sporadic; etc.), duration on a given shift schedule (rotating, seasonal, continuous, etc.), and total number of years of shift-work. To add further complication, these factors can also change for an individual throughout the year.

Once we have an understanding of shift-work exposure, it is then important to understand the individual’s unique internal biological rhythms. This is because some individuals will be better abled at handling morning or night shift based on their internal rhythms. For example, who we colloquially refer to as a ‘morning person’ is usually someone with a short internal day length. For them, it would be much easier to work a morning shift rather than working a night shift when they have a strong biological drive to sleep. The reverse is true for someone who prefers to stay up and wake up late.

So, given the multitude of varying factors, how do you successfully cope with shift work? In Dona’s words, “The current way that we do the grave yard shift is the result of 28 years of figuring out what works for him.” And I think that’s the key. There is no one method to successfully live on a shift-work schedule. Rather, it is important to learn as much as you can and then use that information to help figure out what works for you.

In upcoming posts, we will share with you all the information we learned from Cory and Dona. We will explain Cory’s three different shifts throughout the year and how he has found ways to deal with them. Then, we’ll explain how Dona, who does not have a shift-work schedule, manages her schedule around Cory’s shift.

Check back every Friday for new posts!

References:

- Mattson MP, Allison DB, Fontana L, Harvie M, Longo VD, Malaisse WJ, Mosley M, Notterpek L, Ravussin E, Scheer FA, Seyfried TN, Varady KA, Panda S (2014) Meal frequency and timing in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 16647-16653.

- Asher G, Sassone-Corsi P (2015) Time for food: the intimate interplay between nutrition, metabolism, and the circadian clock. Cell 161: 84-92.

- Gan, Yong, et al. “Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies.” Occupational and environmental medicine (2014): oemed-2014.

share

share