All natural! Low sodium! Fat-free! These are just some of the numerous claims made on food packaging, seeking to convince consumers that a specific product is healthy. But unless you’ve memorized the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations for these labels, it’s not easy to verify their accuracy.

So what can you do to evaluate how healthy a packaged food is? One way is to read the nutrition label and the ingredient list.

Fun Fact: Nutrition labeling began in the United States in the early 1970s, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began requiring nutrition information on packaged foods. The reason was to help inform consumers about what they were eating, and to ensure that consumers had a way to verify any health claims that manufacturers were making about foods.

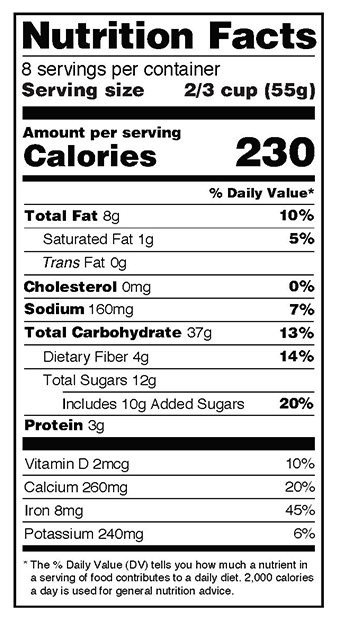

Because foods vary in terms of ingredients, labels can vary somewhat from food to food. That said, labels typically contain these elements:

-

- Serving size (a measured/measurable amount)—so you have a convenient way to understand how much of each nutrient you are getting when you eat a portion.

- Number of servings per container

- Calories—how much energy the serving size represents (see A Closer Look for details), According to the FDA, a food with 100 calories per serving is considered a moderate amount of calories and a food with 400 calories per serving is considered a large amount.

- Macronutrients

o Total Fat, plus subtypes of fat, including Saturated Fat, Unsaturated Fat, Trans Fat, and Cholesterol

o Carbohydrates, including Sugar and Fiber

o Protein

o Sodium—this could also be considered a micronutrient, but since most people’s diets contain far more salt

than is healthy, this is generally listed separately - Micronutrients

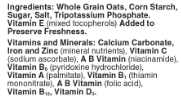

o Vitamins, minerals Pro Tip: Compare foods—two different types of kids’ cereal, for example—and choose the one that has healthier ingredients (whole grains rather than refined grains, or less sugar, to name a couple of criteria).Food packaging is also required to provide an ingredient list. What is in the cereal you’re buying? Note that the ingredients are listed in descending order (largest to smallest) of the amounts in the product.

Pro Tip: When evaluating a product, ignore the flashy wording (heart healthy! high fiber!) and look at the nutrition label and the ingredient list. Look out for red flags on the ingredient list: is sugar one of the first ingredients? Is a flashy claim trying to distract from a problematic ingredient? Maybe “a good source of calcium” also has a lot of sugar. Or a “low fat” product also has lot of sodium.

A Closer Look: Calories vs Kilocalories.

Before you get worried that this is going to get too mathematical or scientific, know that the lesson here will be more about language and history than math or science. Calories and kilocalories are scientific units of energy. For dietary purposes, calories and kilocalories are essentially the same thing. Nutrition labels tell you how many calories a food has, but technically it is telling you how many kilocalories it has (either way, it is telling you how much metabolic energy a food provides.) The reason goes back to scientific definitions from the 1800s: A calorie—notice the lower-case c—was defined as the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of one gram of water (a small amount) by 1 degree Celsius at sea level. For this reason, it was referred to as a “gram-calorie” or “small calorie.” A kilocalorie is a thousand calories (the prefix kilo means thousand). It was defined as the energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 kilogram of water by 1 degree Celsius. (A kilogram is 1,000 grams.) It was sometimes referred to as a “kilogram-calorie” or “large calorie.” In the late 1800s, a scientist proposed using a capital C for the kilocalorie and a lower-case c for the calorie. (Not ideal, since in speaking, you can’t hear the difference!)In 1948, scientists changed the scientific unit of energy from a calorie to a joule. But nutrition labels still use the older term. So “Calories”—with an upper-case C—are actually kilocalories. But the upside is that the math is a little easier when 2 tablespoons of peanut butter has 190 big-C Calories—(kilocalories)—than 190,000 little-c calories!

Sources:

FDA (supplements, updated (2022) nutrition label, 100 and 400 calories statistic)

National Library of Medicine (history of food labeling)

Wikipedia (calories)

share

share